Back in 1775, America was at the other side of a stormy world.

Which meant that, for government folks in London trying to put down a rebellion, if they needed to resupply some 8,000 British troops stationed in Boston, they’d have to contract with a shipping company for lots of boats to carry all the stuff that was needed for the cause, hire the men to sail them, and send them off into the nasty North Atlantic. And then would come the really fun part: crossing their fingers for the next 3-4 months hoping the ships would make it across, and then waiting at least another 3-4 months to find out if they’ve been successful.

Consider, for example, a convoy that departed London in October, 1775. One of the ships in that fleet was a 100-foot, 300-ton vessel named for a place in Jamaica called the Blue Mountain Valley, with a first-time captain and a crew of 15 sailors, carrying such things as coal, potatoes, porter, hay, oats, sheep and pigs. About six weeks into the crossing, the fleet was hammered by gale-force headwinds and walls of water that tore the ship’s rudder loose and sent it on a painfully longer, more southerly course. Some seven weeks later, when the ship finally arrived in America, it was the end of January 1776, most of the hogs were dead, the potatoes were rotten, and the crew had run out of drinking water.

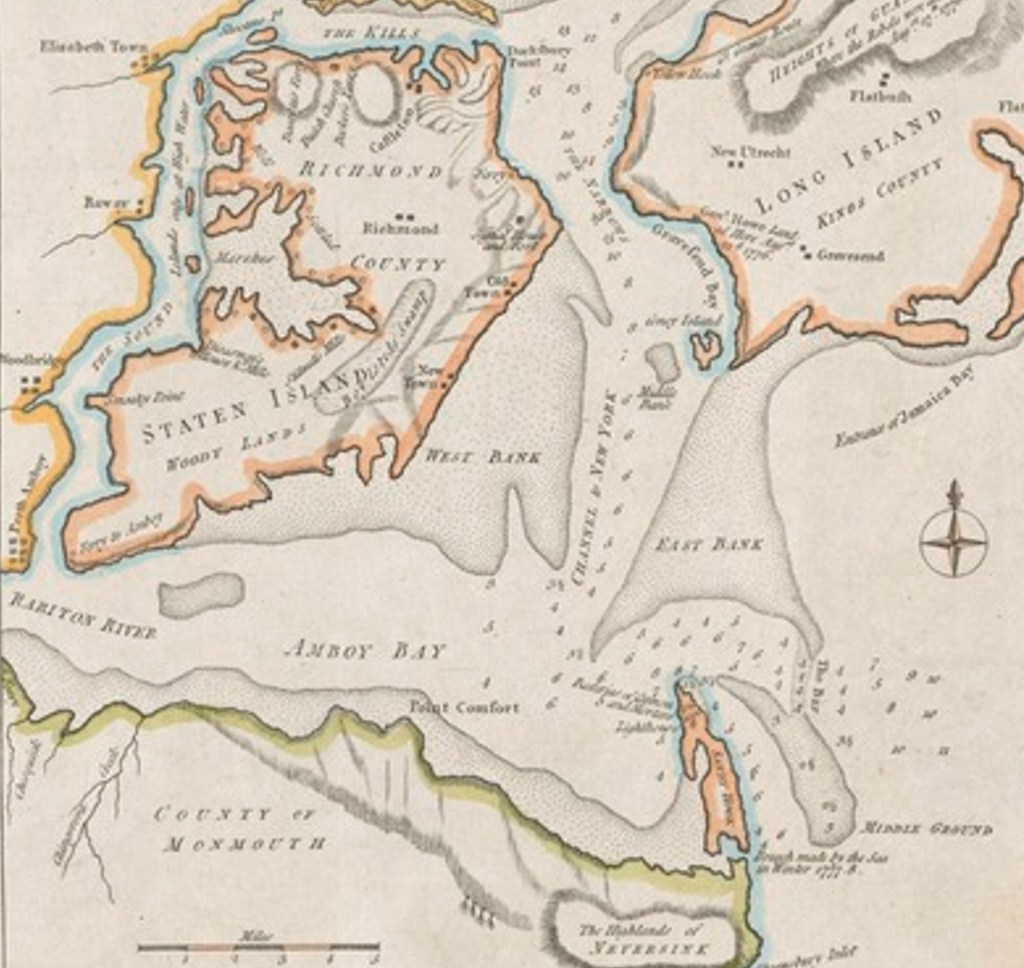

As they dropped anchor, the captain determined that he had arrived off some place called Sandy Hook, New Jersey. OK, so now what? New York was still a rebel-held city, so Blue Mountain Valley looked around for any royal ships in the harbor who might be able to assist them. Soon after, help arrived in the form of a whaling skiff that rowed out from Sandy Hook Lighthouse, led by a captain who promised to bring their distress messages to the HMS Asia anchored nearby. Unfortunately, it was a patriot ruse, the skiff was a rebel craft, and the messages – filled with juicy British military intelligence – ended up in the hands of the local Committee of Safety.

Meanwhile, in the nearby town of Elizabeth, there was this guy with the curious name Lord Stirling. He was a Scottish nobleman actually named William Alexander who had lost his claim to a hereditary title back in Europe, so he had moved to America for greater opportunity and eventually joined the rebel cause. But he demanded that he be referred to by his failed title. He was one of the first to learn about the British ship stranded off Sandy Hook. Acting quickly, Stirling rounded up about 40 men who had been assigned to dig fortifications around New York and marched them to the port of Perth Amboy. There they managed to procure a ship and set out across the water for Sandy Hook.

Shortly thereafter, a second group of 75 more men – the list of which reads like a who’s-who of old established Elizabethtown families – found out what Lord Stirling was doing and set off in hot pursuit in four more boats. When the all these boats converged off Sandy Hook, they were able to overwhelm the crew of the Blue Mountain Valley in a matter of minutes. When they inspected the hold, they were disappointed to not find any arms or ammunition, but they sailed the ship up into Elizabeth Point, imprisoned the crew, offloaded all the inventory, and stripped the ship of its sails and rigging.

On Saturday, January 27, Lord Stirling made the most his victory by sending a letter to John Hancock in Boston declaring that the ship would make a great military asset “and will commodiously carry six 20-pounders and three 10-pounders.” Unfortunately, his optimism was dashed two months later; on March 27, the British navy sent several ships up into Elizabeth Harbor and burned the ship while it sat at anchor.

The fate of the Blue Mountain Valley was not uncommon. Of the 35 ships that left England with her in this particular fleet, only 8 would survive, with some getting blown as far south as St. Kitts.

In the years to come, as the focus of the Revolution shifted south from Boston, and with New Jersey strategically located between the entry points of New York and Philadelphia, there would be ongoing conflict all along the colony’s extensive shoreline.

And there would plenty of opportunities for folks like Lord Stirling to make the most of it.

Leave a comment